Before there was an industry, there were outlaws

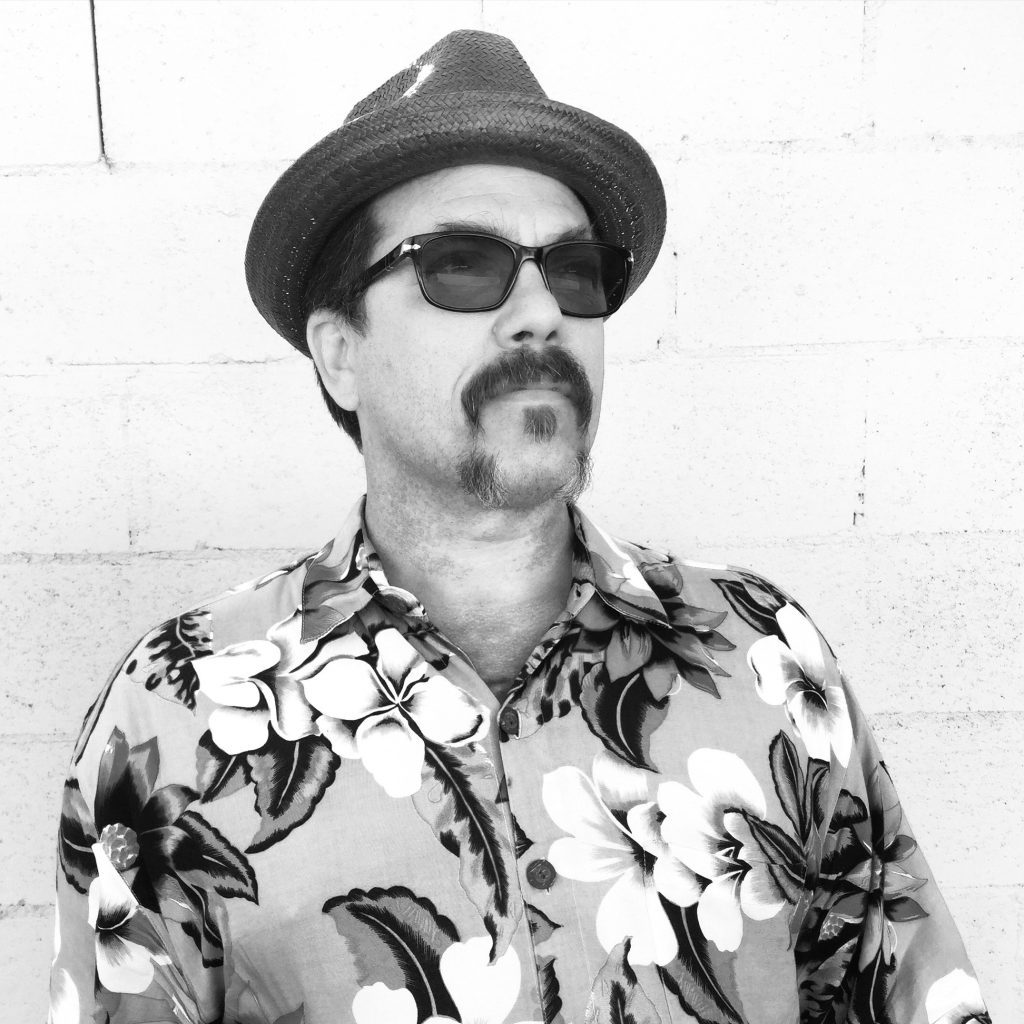

Before cannabis had CEOs, investors, and glossy packaging, it was moved by people who risked everything for the plant. Andrew Lopas, better known as OG Razor, is one of them.

His roots go deep, back to a trading post outside Roswell, New Mexico, where his great-great-grandmother grew and sold cannabis alongside medicinal herbs. He was raised in a world where smoke was medicine and rebellion was survival. His grandmother grew, his uncles knew Ken Kesey and Mountain Girl, and his family teethed babies with mezcal-cannabis tincture.

By age 9, Razor was already hauling water and pulling leaves at secret mountain grows. By his teens, he was running hidden patches in Hollywood, slinging Skunk on the Venice boardwalk, and hopping trains to New York with duffel bags of bud. In the ’80s and ’90s, he hunted landrace genetics around the globe from Morocco, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Nepal, Thailand, and the Hindu Kush, all while dodging feds, fighting off rippers, doing time, and enduring the toll of life underground.

Today, he’s an elder statesman of the craft. Still growing. Still sharp. Still chasing purity in the plant. He’s handing his licenses off to the next generation, but as he puts it, “I haven’t seen anyone grow what I’d smoke yet.”

This is OG Razor, and this is his story.

An Interview with OG Razor

When and where did you first grow cannabis, and did anyone teach you or did you just learn by trying?

My great-great-grandmother grew cannabis and sold it, along with other medicinal herbs, at a trading post outside Roswell, NM. My grandmother was a 15-year-old farm worker in southern New Mexico when she had my mother in 1935. She left my mom with my great-grandmother and went to Southern California to pick citrus in 1940 after pecans stopped paying well.

My mom ended up in Dallas after high school, dancing at the Carousel Club. The owner got her an audition with the Rockettes in NYC because she was 6’6” in heels. She gave birth to me in Brooklyn in 1963, then came to California after my biological father was murdered in NYC.

My grandmother grew marijuana like her mother and grandmother had in New Mexico, except she was doing it in California. She teethed me on a tincture of mezcal and cannabis she made herself. I had aunts and uncles who smoked, and a couple who knew Ken Kesey and Mountain Girl, so I saw a lot of smoke, roaches, and rolling from the time I was a toddler. I was even present during a raid on a farm when I was 4 and got put into protective custody.

I joined my first grow at 9. I got caught trying to steal a plant from my neighbor’s yard in San Bernardino in 1972. I didn’t smoke yet, but I knew that leaf. He knew my uncles from car and motorcycle clubs and told them. They were waiting when I got home from school.

As punishment, I worked weekends that summer at their grows from Lytle Creek to Devore to Fallbrook, carrying water and pulling yellow leaves. I didn’t get to harvest until 1976, the Bicentennial, which was also the year I smuggled a few ounces to NYC for the 4th of July and became a hero to my cousins.

In 1978, I left home after my stepdad caught me trying to grow in the backyard. I ran off to Hollywood with my 16-year-old girlfriend. One of my uncles came to see me, and after I told him about a hidden spot I found, he gave me a dozen female Skunk seedlings.

I planted them in an old horse corral in Beechwood Canyon with help from some retired stuntmen who lived there. I’d read Mountain Girl’s The Primo Plant and talked with botanists from Gubler’s Orchids. I dug holes into layers of old manure, set up a primitive drip system, and ended up with about 40 pounds of bud.

I sold a lot of it in Hollywood and Venice Beach. After stacking enough cash, I bought a fake passport and a KLM ticket from JFK to Amsterdam, smuggling the last pounds to NYC by train-hopping. I sold the rest on the Lower East Side, got a delivery job from the Pope the next year, and just kept improving.

By the mid-’80s, I was in Northern California and sometimes helping on grows on the Big Island, Kona Coast. I used that money to travel, surf, hunt seeds, and learn from people in Morocco, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, Nepal, Thailand, Transkei, Lesotho, Swaziland, Oaxaca, and the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

What is the hardest thing about growing cannabis?

Doing time and losing my oldest daughter in 1984 and my oldest son in 1985. I’ve since reunited with both of them and now have eight grandkids, but the time I lost was the hardest part of choosing to go against the law. I got PTSD from fighting off rippers, getting busted, and being tortured by the feds during diesel therapy in the ’90s.

I’ve come full circle over the last 20 years; I got help, quit drinking, and stopped self-medicating. I do ceremony with the few of us who made it out. Everything else was just work. From 1978 to 1988, I did it solo except for when I started a delivery service and brought in trimmers. Growing was satisfying. Trying to stay alive and out of prison was the hard part. Wondering if my kids were alive and okay while I was on the run was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

*Editor’s note: Diesel therapy refers to a form of punishment enacted by the federal government in which prisoners “are deliberately transported long distances on buses, vans, or planes (powered by diesel engines, hence the name). Instead of being moved efficiently, prisoners are shuffled from facility to facility, sometimes for weeks or months, with little rest, medical care, or access to legal resources.”

Where does the name OG Razor come from?

I was jumped in my neighborhood in 1976 in San Bernardino. I wasn’t a gangbanger I was part of a party clique called Party Life, an affiliate of a car club called Street Life. I deejayed parties, spinning oldies from my mom’s collection and new records from Flatbush Ave when I visited family in Brooklyn.

When I first got jumped in, they gave me a name I didn’t like. A year later, I got jumped by a carload of guys from another hood. My mom wouldn’t let me carry a blade, but when my grandpa passed in ’74, I inherited a cigar box from his nightstand. It had old magic tricks and, hidden in the bottom, a pearl-handled straight razor.

That night, when they rushed me in front of the Circle K, I was getting stomped when I pulled the razor from my sock and swung. Older vatos came running as the guys limped off bleeding. After that, the name “Razor” stuck.

When I started moving weight to other cities around 1987, I was known for Purple Kush seeds I brought back from the Hindu Kush Valley in ’84. I labeled my turkey bags “OG Kush” to keep them separate, and soon everyone just called me OG.

I was a graffiti kid then too, and my bags went everywhere from Phoenix, New Orleans, Minneapolis, Chicago, DC, Philly, Boston, Atlanta, Miami, Tampa. I never mixed Amsterdam seeds in, only my own landrace genetics. By the time I saw people arguing about the name “OG Kush,” I was already living on the run and had moved thousands of pounds. It was never “ocean-grown” or from Florida, at least not my cut.

If you knew your weed came from a guy named Razor, you knew too much. If you knew it came from “the OG,” that could be anybody.

What advice would you give new growers to avoid catastrophe?

Invest in yourself and spend as much time as possible with the plant in as many different environments as you can.

Avoid the grow-shop mentality that every problem needs a bottle, bag, or spray. Everything you need already exists in the ecosystem around you. Every pest has a predator.

Be vigilant and let the plant teach you; she will literally show you what she needs if you pay attention. She wants to be pollinated, but if you create an environment where she won’t, she’ll build a diverse set of trichomes packed with cannabinoids.

Also: learn to make your own hash and charas–dry sift, static, cold water, hand rub. The wisdom of the ancients is in there.

If you could change one thing about the cannabis industry, what would it be?

They made testing a sham.

Back in the day, I’d send the same sample from one cola to SC Labs, Steep Hill, and Sonoma LabWorks under different names just to see if their gear was calibrated. It used to mean something. Now, people pay to play with testing, and a lot still use pesticides or even neem oil.

There’s a lot I’d change. I still grow because I haven’t met anyone who grows something that satisfies me like what I grow. I’m handing my licenses off to the next generation, but I haven’t seen them grow what I’d smoke yet. I just keep moving and hope they catch up.

What’s been your favorite strain to grow and why?

I don’t use the word “strain” I say “genetic.” It just feels more honest.

I don’t have a favorite flavor. Every occasion calls for a different one. I wish I still had seeds from that Skunk my uncles made famous in the ’70s – they’re lost. I haven’t seen the real thing since 1985. Maybe it’s best. It wasn’t the right genetics for these times.

About OG Razor

Andrew Lopas’ life is written in hidden gardens, hand-rubbed hash, and scars from battles most people in this industry can’t even imagine. He never chased fame, and he never needed validation. He built his reputation in the shadows, where only the work mattered.

Today, as he slowly passes the torch to the next generation, Razor stands as a reminder of what this plant has always been about: resilience, rebellion, and respect. The industry will keep evolving, spinning itself slick and sterile, but legends like Razor are the roots, the part that never shows, yet holds everything up. And roots like his don’t die, they just go deeper.